Global activity and trade decelerated at the end of 2018, and data point to continued weakness into 2019.

Slowing activity in the euro area and a sharper than expected deceleration in China could trigger a deeper slowdown in global activity.

Growth in emerging markets and developing economies is projected to stall in 2019, with a weak recovery by commodity exporters accompanied by a deceleration in commodity importers. A recurrence of financial stress could disrupt activity and lead to contagion effects. Trade disputes could escalate or become more widespread, denting activity in the economies involved and leading to negative global spillovers. Slowing activity in the euro area and a sharper than expected deceleration in China could trigger a deeper slowdown in global activity. Policy uncertainty and geopolitical risks remain high and could negatively affect confidence and investment around the world.

Overall Trends

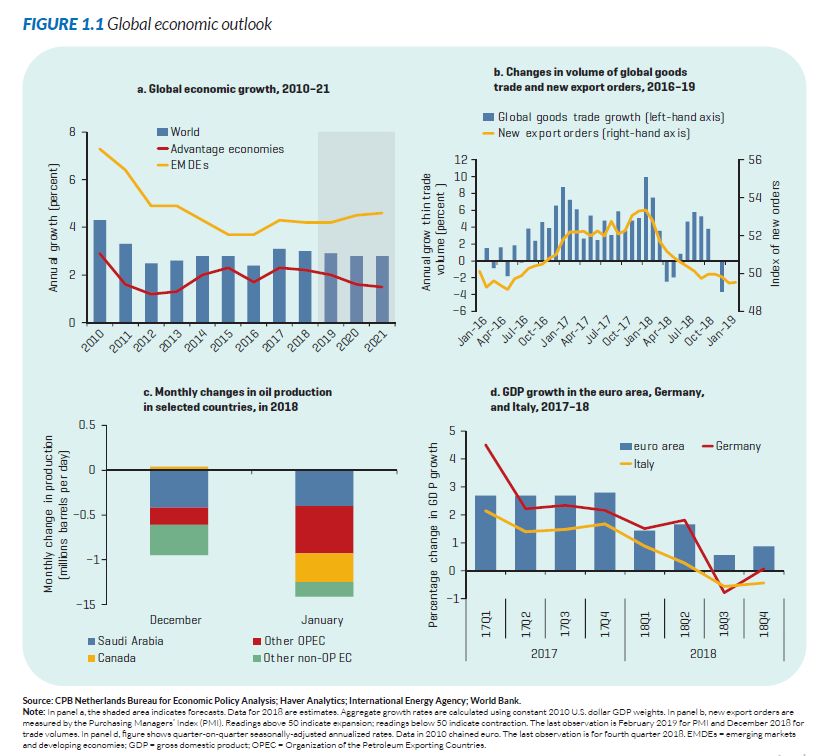

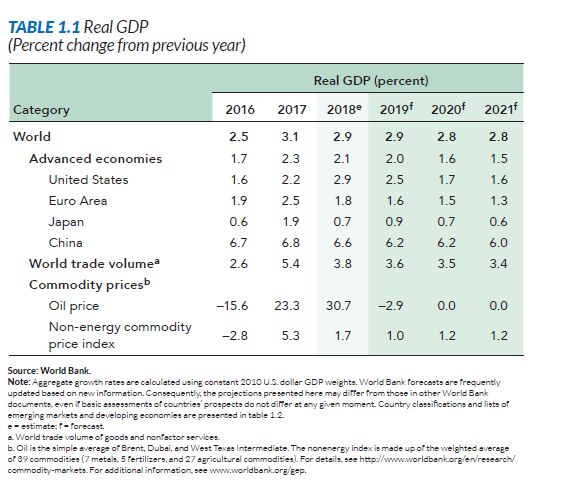

Global growth continues to moderate, amid soft trade and manufacturing activity, reflecting slowdowns in most major economies, as well as in emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs) that experienced substantial financial market pressure, such as Argentina and Turkey. The ongoing weakness is consistent with the January 2019 Global Economic Prospects report, which estimated global growth at 3 percent for 2018 (figure 1.1, panel a). Global inflation trended up during most of 2018, peaking at 2.5 percent (year-over-year) in October before moderating.

Incoming data indicate that global growth may be softening further going into 2019. Global goods trade has been stagnating, with the euro area experiencing its largest contraction in export volumes since the 2009 global financial crisis (figure 1.1, panel b). Over the course of 2018, the pace of industrial production growth declined by more than two-thirds. Several measures of global sentiment have fallen to their lowest level in years. Uncertainty remains elevated, notwithstanding recent optimism that ongoing trade disputes between major economies will be partially resolved.

After tightening throughout most of 2018, global financing conditions have eased somewhat as major central banks responded to deteriorating growth prospects with a more dovish stance, including the Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank, the Bank of England, the Reserve Bank of India, and the People’s Bank of China. Reassessment of the future path of U.S. policy interest rates and inflation have contributed to U.S. long-term yields declining to 2.4 percent after a seven-year peak of 3.2 percent in November. Global equity markets have recovered after bottoming out in late December, despite continuing concerns about softening global growth.

Many EMDEs faced substantial financial market stress or deteriorating market sentiment in 2018. So far in 2019, however, external financing conditions have improved and capital inflows to EMDEs have recovered. After yields on EMDE debt issued on international bond markets rose about 150 basis points in 2018— the third-largest annual increase in the past two decades—sovereign bond spreads reversed and narrowed somewhat, although they remain elevated compared to 2017 levels.

Oil prices have been rising since the beginning of the year, with Brent crude climbing above $65 a barrel in mid- February, driven by a fall in the global oil supply of more than 2 million barrels a day, mainly as a result of planned production cuts by Saudi Arabia and other members of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) (figure 1.1, panel c). Oil prices are forecast to average $67 a barrel in 2019, slightly below the 2018 average.

The prices of metals and most agricultural commodities fell in the second half of 2018, following the imposition of new U.S. tariffs on imports from China; they have been slowly drifting back up in 2019. Negotiations between China and the United States may avert further increases or roll back existing tariffs between the two countries, but trade tensions are likely to persist.

Major Economies

Growth in the U.S. economy increased to 2.9 percent in 2018, mostly reflecting strong domestic demand bolstered by procyclical fiscal stimulus and accommodative monetary policy. Wages and labor productivity are showing signs of picking up. In the coming years, growth is expected to decelerate toward long-term trends, as fiscal stimulus fades and the impact of higher tariffs is felt.

Euro area growth slowed in 2018, falling to 1.8 percent, down from 2.4 percent the year before. Exports softened, reflecting the earlier appreciation of the euro and slowing external demand. German activity decelerated especially rapidly at the end of 2018, and Italy entered a recession (figure TABLE 1.1 )

Incoming data do not point to recovery. Industrial production contracted to its lowest level since 2012, and the Manufacturing Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) dipped to a six-year low.

The United Kingdom is scheduled to exit the European Union at the end of March, but no plans for an orderly withdrawal have yet been agreed upon as the British Parliament has rejected the draft withdrawal treaty negotiated with the European authorities. The exit deadline may be extended. A no-deal Brexit could disrupt activity in the short term and exacerbate financial stability risks in the United Kingdom and abroad. Uncertainty remains high, likely hampering activity.

Growth in China slowed to 6.1 percent (quarter-over-quarter, seasonally adjusted annual rate) in the fourth quarter of 2018, bringing the rate for 2018 to 6.6 percent. Export growth decelerated, contributing to a shrinking current account surplus. Recent data point to further deceleration in 2019, amid ongoing rebalancing away from manufacturing and exports toward consumption and services. Growth is projected to decelerate to 6.2 percent in 2019 and 6.0 percent by 2021, broadly in line with its long-term pace. Supportive fiscal and monetary policies are expected to offset the negative impact of higher tariffs but may have the undesirable effect of slowing the deleveraging and derisking process.

Global Risks

The balance of risks to the global economy is tilted to the downside. The possibility of renewed disorderly financial market developments could further deteriorate growth prospects and spread through EMDEs. Elevated debt in many economies amplifies this risk. If all new tariffs currently under consideration were implemented, they would affect more than 5 percent of global goods trade. The dampening impact of trade tensions involving major economies could be multiplied through global value chains, such as those linking Central Europe to Germany. A sharper than expected deceleration in activity in the euro area and in China could trigger a deeper slowdown in global activity. Policy uncertainty and geopolitical risks remain high and could erode confidence and investment around the world. In the absence of an approved withdrawal agreement, the exit of the United Kingdom from the European Union could be accompanied by significant disruptions to domestic activity and become a source of financial stability risk in other economies.

Europe and central Asia: recent developments and outlook

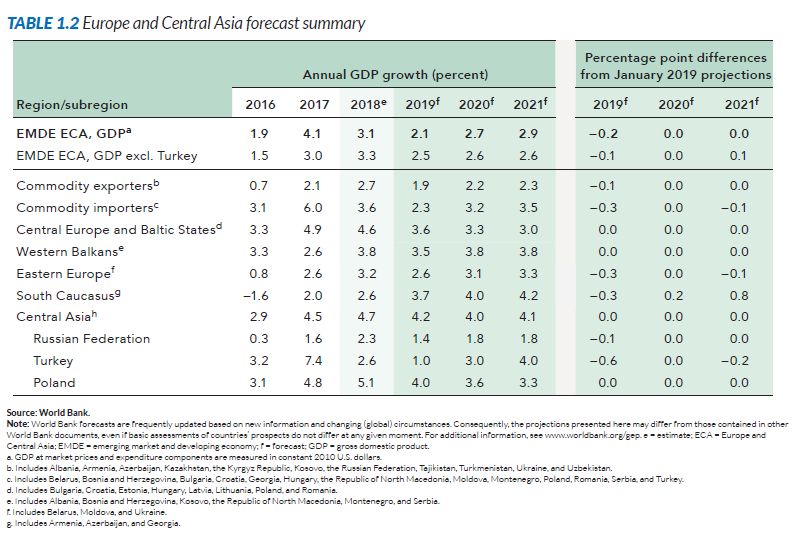

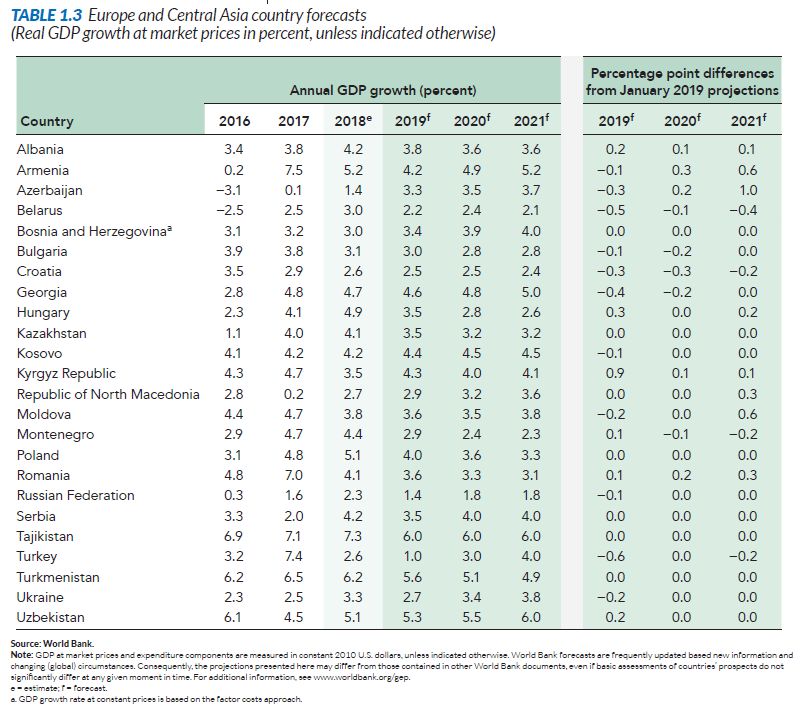

Aggregate growth in EMDEs in Europe and Central Asia (ECA) slowed to an estimated 3.1 percent in 2018, with substantial subregional variations. It is projected to decelerate to 2.1 percent in 2019, mainly as a result of weakness in Turkey, as it experiences the consequences of earlier financial market stress. Regional growth is expected to pick up modestly in 2020–21, as a gradual recovery in Turkey offsets moderating activity in Central Europe. Uneven growth trends underline the regional numbers, reflecting divergence across subregions over the forecast horizon. Key external risks to the region include spillovers from weaker than expected activity in the euro area and an additional escalation of global policy uncertainty, particularly in trade. Renewed financial pressures in Turkey, combined with possible contagion to the rest of the region, could also disrupt growth in the region’s EMDEs.

The possibility of sharp declines in energy prices presents a downside risk to the region’s energy exporters, such as Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and the Russian Federation.

Recent Developments

Growth in the EMDEs of ECA moderated to an average of 3.1 percent in 2018, with wide variation across countries. Upward revisions to gross domestic product (GDP) data for Russia, the largest economy in the region, contributed strongly to regional growth, alongside accelerating growth in Albania, Hungary, Poland, and Serbia. This was offset by weakness in Turkey due to financial market stress. The modest recovery in commodity exporters continued despite the volatility observed in commodity prices toward the end of the year; aggregate growth in commodity importers, excluding Turkey, eased slightly.

In line with general trends among EMDEs, inflation trended up for most of 2018, peaking at 3 percent (year-over-year) in August. It corresponded to the sharp decline in oil prices toward the end of the year. Growth is expected to slide to 2.1 percent in 2019, before recovering to 2.9 percent in 2021. Much of the growth profile reflects developments in Turkey, without which growth is expected to average just 2.6 percent during 2019–21.

Turkey entered a technical recession by the end of 2018, triggered by financial market and currency pressures. The contraction in activity represented a substantial reversal from the peak growth of 11.5 percent in the third quarter of 2017. Market sentiment deteriorated over concerns about rising private sector debt, much of it denominated in foreign currencies, accumulated through current account deficits financed through volatile portfolio capital flows. Accelerating inflation and a perceived delay in monetary tightening led to significant capital outflows from Turkey, with the lira undergoing a nearly 30 percent nominal depreciation against the U.S. dollar. To interrupt the cycle of a depreciating currency contributing to rising inflation and vice versa, the central bank hiked policy interest rates by 16 percentage points over the year to 24 percent by September. Turkish growth is expected to slow to 1.0 percent in 2019, weighed down by shrinking purchasing power, scarce and expensive credit, and low confidence. It is expected to begin to recover by 2020, through gradual improvement in domestic demand and continued strength in net exports, assuming that fiscal and monetary policy avert further sharp falls in the lira and corporate debt restructurings help prevent serious damage to the financial system.

In Russia growth accelerated to a six-year high of 2.3 percent in 2018, despite tightening economic sanctions and financial market pressure. It was supported by the rise in oil prices over most of the year, a solid contribution from net exports, as well as one-off factors, such as energy-related construction projects and the hosting of the World Cup. Throughout most of 2018, consumer price inflation accelerated as a result of the depreciation of the ruble, prompting the central bank to hike the policy interest rate twice toward the end of the year. Tighter monetary policy and a value-added tax hike at the beginning of the year are contributing to decelerating momentum in 2019.

Growth in Central Europe and the Baltics was 4.6 percent in 2018, supported by upwardly revised numbers for Hungary and Poland. Activity in Hungary accelerated to 4.9 percent in 2018, on the back of strong domestic demand from procyclical fiscal stimulus. In Poland, growth reached 5.1 percent in 2018, partly as a result of EU fund transfers and the strongest labor market since the 1990s. In contrast, investment in Romania was subdued, reflecting weak absorption of EU funds, which dampened growth. Central Europe, which is composed mainly of net oil importers, experienced rising inflation throughout 2018 that corresponded to increasing oil prices. The pace of inflation has since slowed, given the sharp decline in oil prices toward the end of the year. The deceleration over the forecast horizon is more pronounced in Central Europe and the Baltics than in other ECA subregions, as growth is expected to slow as a result of a shrinking working-age population, domestic capacity constraints (in Hungary, Poland, Romania, and the Baltics, for example) and tight connections with the slowing euro area economy. Private investment growth has been tepid and could diminish further in the absence of sustained progress on structural reforms.

In the South Caucasus subregion, growth in 2018 was 2.6 percent, backed by robust mining and manufacturing activity. In Armenia, growth expanded to 5.2 percent, slowing in the second half of the year after copper prices dropped. In Azerbaijan, the recovery in domestic demand was slower than previously anticipated, as systemic issues in the financial sector continue to weigh on credit, but a new natural gas pipeline coming on stream is expected to support growth in the coming years. Georgia continued to be characterized by robust domestic demand, although momentum in the third quarter slowed on the back of contracting industrial production growth. Growth in the South Caucasus subregion is projected to strengthen to 4.2 percent by 2021, conditional on continued implementation of domestic reforms.

Growth in Central Asia expanded at a robust 4.7 percent in 2018, the strongest subregional growth among the region’s EMDEs. The recovery from the 2014–16 collapse in oil prices in Kazakhstan has been supported by higher than expected production in the Kashagan oil field and strong domestic demand. In the Kyrgyz Republic, growth eased from 4.7 percent in 2017 to 3.5 percent in 2018, partially as a result of slower gold production. Over the forecast period, growth is projected to moderate to a still robust 4.1 percent by 2020-21 in Central Asia, as the gradual slowdown in the euro area is expected to weigh on export growth in Kazakhstan.

Risks to the Regional Outlook

Although the global economy showed worsening signs of weakness throughout 2018, growth in the region (excluding Turkey) was largely insulated. There are risks that this divergence fades in the face of a sharper than expected deceleration in ECA’s most important trading partner, the euro area. Europe remains the region’s largest trading partner, purchasing the majority of all EMDE ECA exports in 2017. Recent developments point to the predominance of downside risks, with activity weakening sharply in the euro area, especially Germany and Italy, and multiple indicators pointing to continued deceleration going into 2019.

The experience of Turkey in 2018 is a stark reminder of the risk of sudden and widespread shifts in investor sentiment, in particular for countries with large current account deficits or reliance on volatile capital inflows, high external debt loads, or sizable foreign currency-denominated debt as a share of GDP.

Increases in policy uncertainty could undermine confidence in the region and slow growth. Policy disagreements between the European Union and some Central European countries could deter international investors and reduce fiscal transfers. An escalation of international trade restrictions could have a negative impact on the region, given its trade openness and capital linkages. A slowdown or reversal of ongoing structural reforms remains a risk in many countries, especially for Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Ukraine, and Turkey. Tensions over the Syrian Arab Republic or Ukraine could trigger new sanctions.

Long-Term Challenges

Over the next decade, promoting growth for the region’s EMDEs is expected to become more challenging. Demographic trends are worsening rapidly, and productivity and investment growth remain subdued. Growth is expected to slow further in most ECA countries over the next decade (World Bank 2018a). Tighter financing conditions and diminishing economic prospects are expected to deter investment. Unless new technologies can help unleash a productivity revival, productivity growth is expected to remain lackluster. Meanwhile, climate change may impose significant economic costs, especially for countries that rely heavily on agriculture, such as those in Central Asia. Policymakers can adopt a wide range of policy options to mitigate slowing productivity growth and declining working-age populations. This update focuses on one policy - promoting inclusive financial sector development—as a way to promote growth and poverty alleviation.

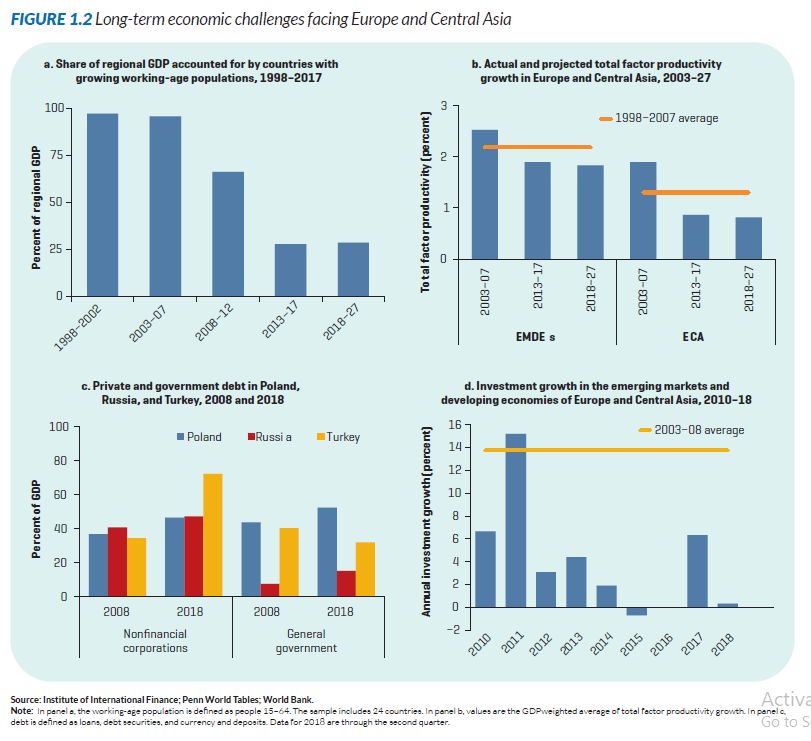

Aging Populations

Working-age population growth among the region’s EMDEs has long been well below the global average for EMDEs. In the late 2000s, it turned negative (figure 1.2, panel a). The shift is attributed to declining fertility rates in the 1990s in the aftermath of the collapse of the Soviet Union, exacerbated by migration to the European Union and Russia. A recent slowing of emigration and rising female labor force participation have only partially mitigated downward trends.

The region can be divided into two parts, based on countries’ stage of demographic transition. Turkey and Central Asia have only recently entered the late stage, characterized by falling fertility and mortality at all ages. The higher-income parts of the ECA region have already reached an advanced stage of aging, with populations declining (Bussolo, Koettl, and Sinnott 2015).

Declining Productivity

Annual trend total factor productivity (TFP) growth in ECA slowed to 0.8 percent in 2013–17, about 0.4 percentage point below the long-term average (figure 1.2, panel b) (World Bank 2018a). The deceleration largely reflected slowdowns in foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows, sectoral reallocation, and reform momentum, combined with aging population and declining business dynamism (World Bank 2018b). In the absence of a sudden productivity boost arising from new technologies, many of the drivers of the productivity slowdown in ECA appear likely to persist over the next decade.

FDI flows have fostered technology transfers and productivity gains among the region’s EMDEs, particularly in Central Europe. However, growth in FDI flows to the region plummeted to 1 percent a year in 2013–16, down from 37 percent in 2005–07, likely adversely affecting TFP growth (EBRD 2015). The reallocation of labor from the agriculture sector to services and industry has been an important source of economy wide productivity gains over the past two decades. In the western part of the region, however, the shift from agricultural to nonagricultural employment slowed after the global financial crisis.

Improvements in the business climate are associated with increasing productivity (World Bank 2018a). Over the past decade, EMDEs in ECA made strides in improving their business environments. As a result, in Central and Eastern Europe, the Western Balkans, and the South Caucasus, indexes of the business environment are approaching the levels in advanced EU countries. Reform momentum appears to have slowed in the mid-2000s, after Central European countries acceded to the European Union. Business climates in Central Asia continue to lag well behind those elsewhere in the region, notwithstanding improvements in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan (World Bank 2019).

Weakening Investment

Investment growth has slowed sharply, from an average of more than 15 percent in the five years before the global financial crisis to an average of 1.6 percent in 2014–18, despite significant increases in debt (figure 1.2, panels c and d).

The causes of investment weakness include declining commodity prices, lower FDI inflows, and lower long-term growth expectations. A sudden tightening of financial conditions could further weigh on investment, particularly for countries with high levels of debt that is denominated in foreign currency, short term, or at variable rates. In countries where the banking system is weak or has deteriorating asset quality (such as Belarus, Croatia, Kazakhstan, Russia, and Ukraine), a “sovereign-bank nexus” could amplify the impact of financial disruptions if bank holdings of government debt combine with government guarantees to the financial system to intertwine the health of banks and sovereigns (World Bank 2018c).

Climate Change

Climate change is contributing to droughts, floods, more intense and frequent natural disasters, and rising sea levels, with the poorest and most vulnerable people often hit hardest. Changes in rainfall patterns, rising temperatures, droughts, and floods have serious implications for countries with large agriculture sectors. Central Asia is especially vulnerable because of its aridity, previous underinvestment in infrastructure, high frequency of natural disasters, reliance on glaciers for water supply, and legacy of Soviet-era environmental mismanagement (UNDP 2018). Changes in sea level will affect many countries. Poland’s heavily populated Baltic coast is vulnerable to rising sea levels. The Black Sea has seen a significant rise in sea level, which is threatening the many ports and towns along the coasts of Georgia, Russia, and Ukraine. As a result of increased surface evaporation, water levels in the Caspian Sea are projected to drop by approximately 6 meters by the end of the 21st century, imperiling fish stocks and coastal infrastructure (Fay, Block, and Ebinger 2010).

Policy Options for Responding to Long-Term Challenges

A wide range of policy options is available to help address the region’s long-term challenges. Filling the region’s investment gaps—estimated to be equivalent to 1.3 percent of GDP—could boost productivity (EBRD 2015). Public firms tend to be less efficient than private firms in ECA; privatization therefore presents an opportunity to raise economy wide productivity, especially if it is accompanied by improved management and corporate governance.

Promoting FDI and other forms of connectivity could accelerate technology absorption and speed convergence with advanced economies (Gould 2018). Greater participation in global value chains is associated with faster productivity growth. Some countries have already integrated into the German supply chain. Countries in the South Caucasus and Central Asia could make similar progress through greater East-West connectivity. ECA countries could mitigate the impact of declining populations by increasing labor force participation—by providing better access to childcare services or attracting and retaining skilled labor, for example. Investments in human capital— both health and education—are also key in promoting productivity.

Financial Sector Development

Finance is central to development. Well-functioning financial systems contribute to growth and poverty alleviation by mobilizing and pooling resources, allocating capital to its most efficient uses, monitoring these investments after they have been made, and diversifying and managing risk. To be able to perform these functions, financial systems need to be deep, efficient and stable. For all segments of the society to benefit from these services, they also need to be inclusive.

Inclusive financial sector development can contribute to economic development by promoting individuals’ investments in their health, education, and businesses. Greater financial inclusion can also help allocate the savings of an aging population and increase access to finance. But not all financial services are appropriate for everyone, and -especially for credit- there is a risk of overextension. Promoting financial inclusion is a responsible and sustainable way requires strong regulation and supervision to prevent potential crises that can accompany a rapidly-growing financial system (Gould and Melecky 2017; World Bank forthcoming). The feature chapter of this update examines recent trends and identifies many remaining challenges in promoting financial inclusion in ECA countries.

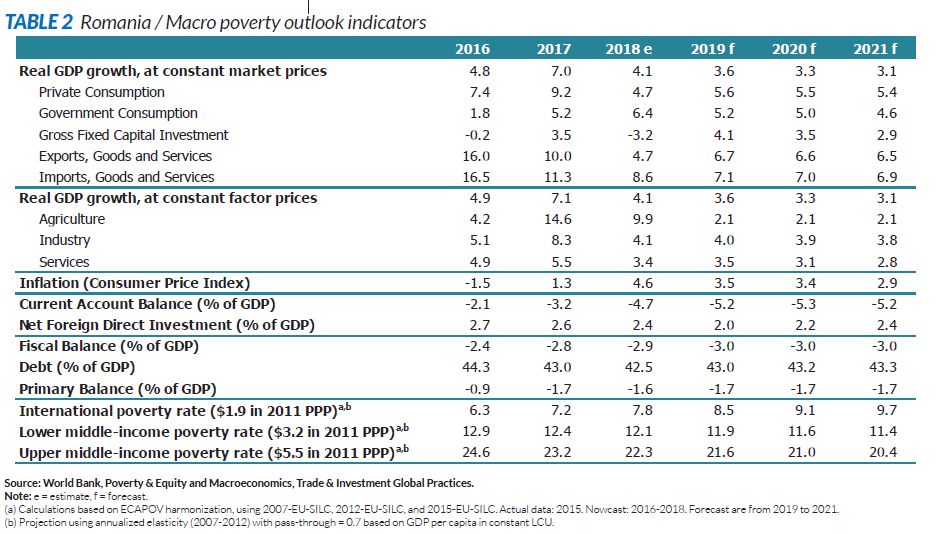

Economic growth remained strong at 4.1 percent in 2018, largely in line with the country’s long-term potential. Growth was driven by private consumption, supported by expansionary fiscal policy, while investment was subdued. Improved labor market outcomes, including historically low unemployment, have contributed to the further reduction of poverty. Risks to the growth outlook have increased, stemming mainly from weaker demand from the major export markets, a tightening labor market and fiscal policy uncertainties.

Recent developments

The economy grew by 4.1 percent in 2018, in line with potential but down from a post-crisis high of 7 percent in 2017. Growth was driven by private consumption (up 4.7 percent yoy) supported by increases in the minimum and public sector wages and pensions. Investment underperformed, contracting by 3.2 percent yoy, owing to weak performance in construction and a slowdown in industry.

Exports grew by 4.7 percent yoy reflecting weaker demand from the major export markets, while imports remained strong (up 8.6 percent). On the production side, ICT (up 7 percent yoy) and industry (up 4.1 percent yoy) were the main drivers. The fiscal deficit was 2.9 percent of GDP in 2018, but fiscal policy continued to be pro-cyclical. Increases in public wages and pensions led to a 23.7 percent hike in the public sector wage bill and a 16.5 percent increase in current budget spending. Social contribution revenues were strong (up 36.8 percent yoy) reflecting the legal transfer of the social contributions from employers to employees and improved collection.

The impact was partially offset by the 24.8 percent contraction in personal income tax revenues from the reduction of the income tax rate from 16 to 10 percent in January 2018. The boost in consumption led to a widening of the current account deficit to 4.7 percent of GDP mainly on the back of an increase in the goods trade deficit. FDI inflows amounted to 2.4 percent of GDP in 2018. The domestic demand pressures contributed to a temporary hike in inflation to 5.4 percent in May 2018, prompting the NBR to increase its policy rate by 75 ppts cumulatively (to 2.5 percent) in three rounds in 2018. Slowing consumption growth in H2 2018 eventually brought inflation down to 3.3 in December. The labor market benefited from economic growth, with unemployment falling to 4.2 percent in December 2018, a 27-year low, and real wages increasing by 8.9 percent yoy.

Nonetheless, the low employment rate (66.2 percent, below the EU average of 69.1 percent) and high youth unemployment (16.4 percent in Q3 2018) reflect persistent rigidities in the labor market. A key driver of low employment is low female participation - 55.8 percent in 2017, the fifth lowest rate in the EU - and one of the highest participation gender gaps. In line with robust economic growth, boost in private consumption and labor market improvements, the poverty rate corresponding to upper middle-income countries (using the $5.50/day 2011 PPP poverty line) is forecast to have declined to 22.3 percent in 2018, from 25.6 percent in 2015, after peaking at nearly 32 percent in 2012.

The incomes of the bottom 40 were boosted by employment gains in sectors with a large share of low-skilled workers. The impact has been stronger for those in the bottom 8 0 percent of the income distribution, who have seen an increasing share of total incomes over this period. Tightening labor markets and minimum wage increases have contributed to a reduction in inequality, reversing a rise in the Gini index seen between 2010 and2014, although Romania’s inequality indicators remain high in the EU context. Since 2014 poverty has declined in both rural and urban areas, but in 2016 estimated poverty rates in rural areas remained 6 times higher than in cities and just over twice as high as in towns and suburbs.

Outlook

The economy is projected to grow at a slower pace over the medium term, reflecting the closing output gap, labor market tightening and fiscal policy uncertainties.

Growth in the Western Balkans picked up to 3.8 percent in 2018, up from 2.6 percent the previous year. In Serbia, the economy rebounded from weather-related disruptions in 2018 and benefited from strong job creation. Activity in Albania and Montenegro was solid, thanks to robust industrial production growth, as well as a strong tourism season. Growth in the Western Balkans is envisaged to moderate to 3.5 percent in 2019 and grow to 3.8 percent by 2020- 21, but the outlook is predicated on political stability and policy uncertainty remaining in check. Infrastructure projects and investment in the subregion will help deliver robust growth in some economies (for example, Kosovo and Serbia), while a deceleration in public and private investment will taper activity in others (for example, Albania and Montenegro).

Fiscal measures promoted at end-December 2018 risk slowing the economy further in 2019 and beyond. These measures include the introduction of a tax on bank assets, a turnover tax for companies in energy and telecoms; and measures to increase the capitalization of the second pension pillar funds. The government has committed to maintaining the budget deficit within 3 percent of GDP in 2019. However, the fiscal measures passed in 2017 and 2018 have put pressure on the consolidated budget deficit and reduced the available fiscal space for investment. Further planned increases in pensions and public wages will exacerbate these pressures. Widening of the fiscal deficit to 3 percent of GDP, coupled with an increase in borrowing costs and a slowdown in growth would push public debt from 4 3 percent of GDP in 2017 to 43.3 percent at end-2021, still among the lowest ratios in the EU. After peaking in the spring of 2018, inflation is expected to stabilize at current levels of around 3.5 percent, reflecting slowing growth in domestic demand. The expected slowdown in Romania’s traditional export markets, coupled with persistently high international commodity prices, would contribute to a further widening of the current account deficit to5.2 percent in 2019 from 4.7 percent in 2018. Strong private consumption aided by the expansionary fiscal policy and continued growth in real wages, partly supported by minimum wage increases, should boost real incomes and lead to further declines in poverty incidence. However, these gains will be eroded by Romania’s fiscal system, which deepens rather than alleviates poverty due to the large regressive impact of indirect taxation. The $5.50/day 2011 PPP poverty rate is projected to decline to 21.6 percent in 2019, 21.0 per-cent in 2020, and 20.4 percent in 2021.

Risks and challenges

The slowdown in Romania’s export markets in the EU, mainly Germany and Italy, could adversely affect growth and investment. Negative effects could be exacerbated by fiscal policy uncertainties, coupled with a tightening labor market. The partial decoupling of real wage growth and productivity could also affect Romania’s competitiveness, putting supplementary upward pressures on the current account deficit.

Renewed efforts are needed to improve labor participation, in particular to address labor market barriers for women, and to tackle higher unemployment among the youth and those with secondary education or less, helping to ease labor supply constraints and improve the sustainability of growth. Over the medium term, fiscal policy should be re-balanced from boosting consumption to mobilizing investment, primarily from EU funds, with the aim of supporting a sustainable EU convergence path and social inclusion. Reforms in public administration and SOEs, increased regulatory predictability, reduction in of social and spatial discrepancies should be key government priorities.

The macroeconomic forecasts presented in this report are the result of an iterative process involving World Bank staff from the Macroeconomics, Trade, and Investment Global Practice; regional and country offices; and the Europe and Central Asia Chief Economist’s office. This process incorporates data, macro econometric models, and judgment. The full report can be downloaded here.