Romania’s transformation has been “a tale of two Romanias”—one urban, dynamic, and integrated with the EU; the other rural, poor, and isolated. The reforms spurred by EU accession boosted productivity and integrated Romania into the EU economic space. GDP per capita rose from 30 percent of the EU average in 1995 to 59 percent in 2016. Today, more than 70 percent of the country’s exports go to the EU, and their technological complexity is increasing rapidly. Yet Romania remains the country in the EU with by far the largest share of poor people, with more than a quarter of the population living on less than $5.50 a day. There are widening disparities in economic opportunity and poverty, across regions and between urban and rural areas. While Bucharest has exceeded the EU average income per capita, and many secondary cities are becoming hubs of prosperity and innovation, Romania remains one of the least urbanized countries in the EU. Access to public services remains constrained for many citizens, particularly in rural areas, and there is a large infrastructure gap. This is a drag on the international competitiveness of the more dynamic Romania; and it limits economic opportunities for the other Romania in lagging and rural areas.

An oscillating approach to reforms lies at the root of Romania’s lack of shared prosperity. Economic growth since 1990 has been among the most volatile in the EU, largely because of the hesitant approach to structural reforms, with periods of enthusiasm alternating with periods of stagnation and even reform reversal. Growth often had a narrow base, and was driven by consumption. Weak commitment to fiscal discipline frequently led to macroeconomic imbalances that required sharp subsequent corrections. Moreover, owing to poorly targeted social safety nets, the cost of the adjustments was disproportionately borne by the most vulnerable people. As a result, poverty rates have remained distinctively high given Romania’s income level, and social disparities have continued to widen.

Institutional challenges must be addressed to bridge the gap between the two Romanias. Growth is constrained by weak commitment to policy implementation, creating a poor business environment and the misallocation of resources to politically connected firms. Equal opportunities are constrained by weak local service delivery and an inability to ensure sufficient local funding because of patronage-based politics. Resilience to natural disasters and climate change is constrained by lack of coordination between central and local authorities. As argued in this report, Romania has no choice but to address these institutional challenges if it is to sustain the impressive growth performance of recent years, share prosperity among all its citizens, and improve its resilience to natural hazards.

Sustaining growth

Sustained growth depends on increasing the quantity and quality of labor and capital, as well as on improving economic efficiency. After witnessing a sharp output collapse following the global financial crisis, in recent years Romania has become one of the fastest growing economies in Europe. Yet, the quality of growth has deteriorated, with labor productivity growth slowing from 8.5 percent on average before the crisis to an annual average of about 2.5 percent after the crisis—the largest drop in Central Europe. To sustain growth in the medium term and keep converging with the living standards of Europe, Romania needs to revamp the drivers of growth, with more and better labor, better capital investment, and more efficient allocation of resources.

Labor force participation is too low to mitigate the effects of aging and emigration. Between 2000 and 2017, Romania’s population fell from 22.8 to 19.6 million, and is expected to continue falling. With an estimated 3 to 5 million Romanians living and working abroad, in 2010 Romania ranked as the tenth main country of origin of migration flows in the G20, with highly educated emigrants accounting for 26.6 percent of the total. The shrinking quantity of labor is not compensated for by greater labor force participation, which—with an overall rate of 68.8 percent and 60.2 percent for women in 2017—is one of the lowest in the EU.

The skills of the workforce are inadequate for the needs of a modern economy. Over the last two decades, Romania’s economy has become increasingly sophisticated, with its exports switching from labor-intensive, low-technology sectors to more advanced sectors like automotive, machinery, and electronic equipment. The skills of the workforce are struggling to keep up with the needs of a more sophisticated economy. Tertiary education attainment, at 25.6 percent in 2016, is the lowest in the EU, and Romania lags in the number of graduates in STEM disciplines. Skills shortages are also reported in skilled manual occupations, partially reflecting the low development of vocational training, and key socio-emotional skills are found to be particularly lacking.

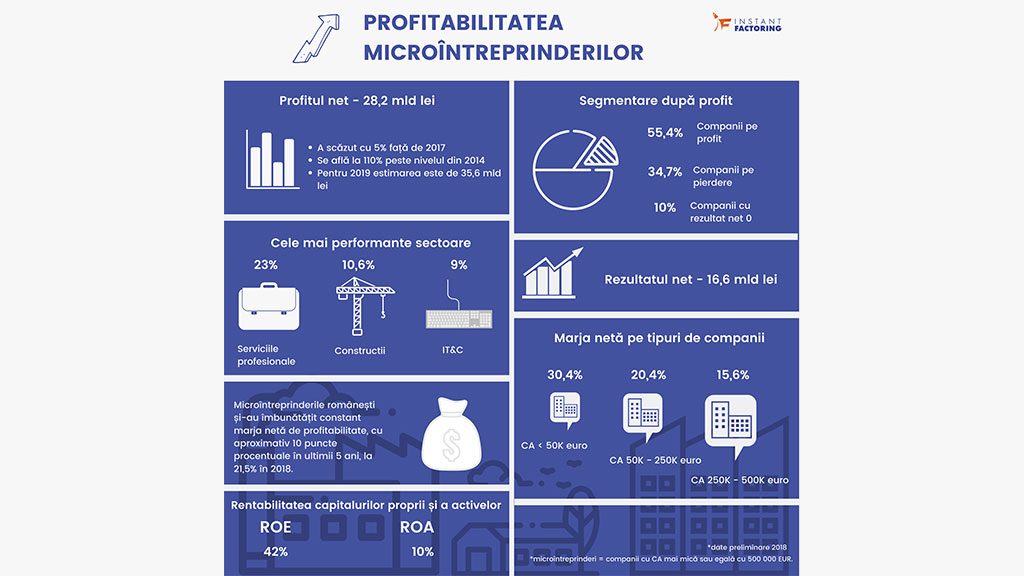

Private investment has remained at fairly high levels, but a shallow financial sector limits the availability of long-term finance. Romania invested, on average, 25 percent of GDP between 2000 and 2016, mostly in manufacturing and non-residential construction, with private sector investment accounting for more than 75 percent of the total. However, foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows—a conduit for the transfer of capital, access to modern technologies, competition, and better managerial skills—remain below pre-crisis levels. The banking sector is the main financial intermediary, but bank loans to private enterprises amount to a meagre 12.7 percent of GDP. Overall, a shallow and bank-centric financial sector limits the availability of long-term finance for investment.

Public investment has not played a supportive role because of institutional weaknesses. Romania ranks 102nd out of 137 countries in the quality of its transport infrastructure, according to the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Report 2017–2018. Clearly, high levels of public investment, boosted by the large influx of EU funds since EU accession in 2007, have not yielded the expected results in terms of quality and quantity of transport infrastructure. Insufficient institutional coordination, ineffective policy implementation and monitoring, politicization of decision making, poor human resources policies in public administration, and delays in implementing results-based budgeting have contributed to weak public investment performance.

An unpredictable business environment and the large presence of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in the economy undermine the efficient allocation of resources. Key factors behind the slowdown in productivity since 2008 include access to credit and red tape. The unpredictability of the business environment—a direct consequence of institutional failures—is a significant challenge to business operations. For example, in recent years, businesses were faced with many fiscal measures introduced, and then reversed, which severely impacted their ability to plan operations, including investments.

According to the European Investment Bank (EIB) investment survey 2016, “political and regulatory climate” was the top factor negatively impacting firms’ ability to carry out planned investment for 47 percent of Romanian firms. Poor corporate governance of SOEs is another source of inefficiency, dragging down aggregate productivity both directly in the sectors where SOEs are active, and indirectly through the inefficient provision of inputs to other sectors of the economy.

Sharing prosperity

Romania’s prosperity is not equally shared, as the bottom 40 is largely disconnected from the drivers of growth. Close to half of the people at the bottom 40 percent of the income distribution do not work, and another 28 percent remain engaged in subsistence agriculture. Improvements in income before the crisis were driven by a large-scale labor reallocation from agriculture to low-skilled sectors, but those gains were reversed as the same sectors shed large numbers of jobs during the crisis. Poverty is highly concentrated in rural areas, where the labor force is highly unskilled and where there are few opportunities. Low internal mobility further reinforces Romania’s dual development challenge—less than 2 percent of the population reports having moved in the past five years, implying that structural constraints inhibit internal mobility toward economic opportunities. Lack of institutional commitments to long-term policies—and an inability to ensure sufficient local funding as a result of patronage-based politics—are at the core of slow and uneven progress in meeting the human capital challenges. They also inhibit other reforms that could alleviate structural constraints to job growth and improve the effectiveness of the social protection system.

Inequality in opportunities persists, holding up transitions to more productive jobs and widening the human capital gap. Forty percent of 15-year-old Romanian students are functionally illiterate; and early school-leaving—at 18.5 percent—is one of the highest in the EU. The health care system is overregulated, creating barriers in access to services, and a weak primary care system disproportionately affects the poor and vulnerable. The challenge is particularly severe for the Roma people, who have a 28 percent employment rate and a staggeringly high poverty rate of 70 percent. Maintaining a focus on equal opportunities, targeting efforts to reach marginalized communities, and enhancing mobility through infrastructure investments can substantially increase the potential for agglomeration and more effectively reduce regional disparities.

Improvements in the labor market have been slow, constraining productive employment. A broader labor shortage exists amid the low labor force participation of key demographic groups. Existing labor market and family policies reinforce the low participation rate of women, as strong gender norms continue to place the burden of child and elderly care on women. And a large share of the workforce is trapped in low-productivity agricultural and other informal activities, leading to the underutilization and misallocation of labor. Reducing rural poverty requires tackling the large agricultural productivity gap caused by fragmented farm structures and low access to credit and extension services. Meanwhile, relatively few in the bottom 40 hold formal jobs that would benefit from minimum wage increases, but the potential cost of the policy could be high if it is not accompanied by corresponding increases in labor productivity.

Equity requires a robust social safety net for those falling behind and high-quality public services for all. Social spending is the second-lowest in the EU, at 14.4 percent of GDP. It is also inefficient and increasingly skewed toward pensions. This makes it less effective at reaching the people most in need, as pension coverage among the rural poor is low and falling. The provision of social services that involve social protection, employment, education, and healthcare is fragmented and sparse, especially in rural areas where the need is the greatest. Formalizing property rights could provide the foundation for boosting private sector activities, including the development of agribusinesses, and could promote spatial development and public infrastructure. Improving access to public services remains an urgent priority, as 22 percent of the population still lack access to potable water and 32 percent live without a flush toilet. Most of the gap is in rural areas.

Improving resilience

Natural hazards pose a great challenge to the Romanian economy and disproportionately affect the poor. Romania stands out for its vulnerability to risks from earthquakes, floods, and droughts, the latter two intensified by climate change. These disaster risks disproportionately affect poorer counties. The potential damage to natural, physical, and human assets can curtail economic growth, jeopardize fiscal sustainability, and negatively affect the well-being of Romania’s population. Improving resilience to natural disasters will require institutional efforts on disaster preparedness and risk reduction, and the mainstreaming of climate change in policy considerations.

Strengthening institutions

Despite progress, particularly in judicial anti-corruption work, fundamental institutions remain weak and constrain progress in inclusive growth. Reforms stemming from the EU accession process have not resulted in transformative institutional improvements. Past top-down efforts have not alleviated deeper systemic problems, as corruption is a consequence of deep-rooted systemic deficiencies in state behavior and in state–society interactions.

Functional challenges hinder inclusive growth and resilience. The public sector struggles to credibly commit to reforms and policy implementation, which creates a difficult environment for firms. This is evidenced by the frequent use of “emergency ordinances” and frequent changes to fiscal legislation. Weak commitment to deliver on long-term objectives undermines service delivery and equality of opportunity. Fragmentation of sectoral responsibilities has led to poor inter-sectoral coordination and diffuse accountability, further limited by poor access to information. The most notable example of weak coordination is found in deep inefficiencies in public spending and bottlenecks in the absorption of EU funds. Corruption undermines cooperation and trust in the state, leading to citizen disengagement.

Underlying power asymmetries cause corruption and poor governance. The causes of these challenges can be traced back to state capture by vested interests and a pervasive clientelism that leads to resource misallocation—as seen in public procurement contracts—and that limits innovation. Clientelism and patronage in the civil service undermine public sector capacity. The civil service remains highly politicized, while the non-meritocratic system leads to a lack of trust and weakens the innovation ecosystem.

Given the complex governance challenges, increasing transparency to enhance accountability would be an important step to improve implementation capacity and oversight. Developing a management framework for public investment for both budgetary and EU funds could significantly improve the predictability of fiscal policies and public investment efficiency. Further, reducing bureaucratic requirements could help shift anticorruption efforts toward prevention and return trust in the state. Reforming the civil service by depoliticizing public administration and creating professional senior management would reduce the bottlenecks in decision making.

The key lesson from this diagnostic is that despite impressive economic growth, achieving shared prosperity and sustainable welfare improvements will remain a distant reality if Romania does not address its governance challenges. Identifying governance failures as the binding development constraint sheds light on why economic growth continues to be volatile and noninclusive. Concerted efforts are needed to enhance commitment to long-term policy goals, while future policies need to acknowledge and address the underlying institutional challenges. Resolving these will be a long and difficult process, but the potential rewards will be high. This would also help Romania counter the consequences of a shrinking and aging population, and allow those at the bottom to contribute more actively to economic growth, which could trigger a virtuous cycle of inclusive growth and development.

Reform priorities for inclusive growth

This Systematic Country Diagnostic (SCD) proposes a number of development priorities for Romania that will help enhance equity and shared prosperity. Four broad areas of priority are identified: (i) increase the effectiveness and efficiency of the state in public service delivery; (ii) catalyze private sector growth and competitiveness; (iii) ensure equal opportunities for all; and (iv) build resilience for sustainable growth. The governance priorities are considered as prerequisites, whereas the other three areas proposed are intended to be complementary and mutually supportive. The complete list of priorities is very long, as difficult challenges remain in many key areas. Priorities are identified based on their potential for reducing poverty, boosting shared prosperity, and advancing toward the goal. A table with a detailed list of priorities is presented in Chapter 6. These priorities will inform the World Bank Group’s engagement in Romania for the period 2019–2023.

A TALE OF TWO ROMANIAS

Romania’s transformation has been a tale of two Romanias: one urban, dynamic, and integrated with the EU; the other rural, poor, and isolated. Reforms spurred by EU accession boosted productivity and integrated Romania into the EU economic space. GDP per capita rose from 30 percent of the EU average in 1995 to 59 percent in 2016. Today, more than 70 percent of the country’s exports go to the EU, and their technological complexity is increasing rapidly. Internet speed is among the fastest in the world and the gross value added of the information and communications technology (ICT) sector in GDP, at 5.9 percent in 2016, is among the highest in the EU. Yet Romania remains the country in the Union with by far the largest share of poor people, when measured by the $5.50 per day poverty line (2011 purchasing power parity) (Figure 1). More than a quarter of the population—26 percent in 2015—lives on less than $5.50 a day. This is more than double the rate for Bulgaria (12 percent). There are widening disparities in economic opportunity and poverty across regions and between urban and rural areas. While Bucharest has already exceeded the EU average income per capita and many secondary cities are becoming hubs of prosperity and innovation, Romania remains one of the least urbanized countries in the EU, with only 55 percent of people living in cities. Overall, access to public services remains constrained for many citizens, particularly in rural areas, and there is a large infrastructure gap, which is a drag on the international competitiveness of the more dynamic Romania and limits economic opportunities for the other Romania in lagging and rural areas.

Romania’s dual development is a manifestation of a lack of shared prosperity and the result of institutional failures, which lie at the root of the volatile and not sufficiently inclusive growth of the past three decades. Economic growth since 1990 has been among the most volatile in the EU, largely as a result of the hesitant approach to structural reforms, with periods of enthusiasm alternating with periods of stagnation and even reform reversal. Growth often had a narrow base and was driven by consumption. Weak commitment to fiscal discipline frequently led to macroeconomic imbalances that required sharp subsequent corrections. Moreover, owing to poorly targeted social safety nets, the cost of the adjustments was disproportionately borne by the most vulnerable. As a result, poverty rates have remained distinctively high for Romania’s income level, and social disparities have been widening.

In the first phase of transition, institutional legacies from the old order led to a late start of reforms, while the opening of the economy led to a large contraction in output and rapidly increasing inequality. In the early 1990s, prices were liberalized and the legal framework for private property and a market-based economy was established. Often guided by the desire to protect powerful vested interests, the authorities tried to preserve employment in the state-owned enterprise (SOE) sector and in the public administration, hampering the development of private enterprise and the reallocation of labor to more productive jobs. Consequently, real wages declined as productivity stagnated and inflation surged. Voucher-based mass privatization was launched in 1995, with limited success. The adoption of an early retirement program in 1994 led to a significant drop in employment. Low job creation led to long-term unemployment, with ensuing high external migration, and agriculture became the employer of last resort. Income disparities deteriorated rapidly, and the Gini inequality index increased from 0.2 to 0.3 in a decade.

The run-up to EU accession in 2007 provided an anchor for institutional transformation, but growth remained uneven and inequality continued to worsen. Romania was invited to open negotiations with the EU in December 1999. Until Romania joined in January 2007, EU accession remained an anchor for reforms, providing momentum for the privatization and restructuring of SOEs and for regulatory and judiciary reforms. Output gradually recovered, and until 2008 the country enjoyed high but volatile growth. Productivity increased as foreign direct investment (FDI) began to come into the manufacturing sector, bringing new technologies, modern processes, and access to external markets. Unemployment was on a declining trend, but youth and long-term unemployment remained elevated. Skills and labor shortages became increasingly widespread. High inactivity persisted stubbornly, particularly among women. Gains in labor force participation were modest overall. While there were important improvements in the well-being of the population, stark differences remained across social groups and regions of the country, and between urban and rural areas. Inequality increased further, as large categories of people—the Roma in particular—continued to be excluded from the benefits of growth.

Although output has recovered since 2008, institutional shortcomings have compounded the effects of the crisis, contributing to significant setbacks in poverty reduction, and are again leading to macroeconomic imbalances. In the run-up to the 2008 crisis, pro-cyclical fiscal policies and sizeable capital inflows caused widening macroeconomic imbalances, leading to a 7.1 percent contraction in GDP in 2009 (Figure 2). This caused large-scale job losses, with many of the poor falling back on agriculture as a means of last resort. The construction sector, which contributed significantly to job growth before the crisis, was hit particularly hard, and job creation in low-skilled sectors has been modest since then. Fiscal consolidation during 2009–2015 has helped place economic growth on a strong footing. However, lack of commitment and underfunding for the delivery of public services and poor targeting of social programs have contributed to the negative income growth of the bottom 40 percent of the income distribution (the so-called bottom 40) in 2009–2015, with poverty remaining above pre-crisis levels, and inequality still among the highest in the EU (Figure 3). Furthermore, since 2016, a wavering commitment to fiscal discipline has led to widening macroeconomic imbalances, again exposing Romania to the risks of future shocks.

The process of institutional convergence with the EU remains incomplete, and the poor functioning of institutions is at the root of Romania’s dual development. EU accession led to substantial de jure reforms, which were often subsequently reversed or weakly implemented. As a result, Romania still performs below European averages in many key areas of governance, including government effectiveness, voice and accountability, regulatory quality, and political stability. While important steps have been taken to address corruption, citizens still perceive it as high and widespread. An incomplete institutional transition and high political volatility over the past 25 years have reduced the trust in the state, effectively undermining the social contract. This has limited the government’s ability to implement important public policies to boost the economy’s growth potential, create equal opportunities and jobs for all citizens, and improve the country’s resilience to natural disasters.

Governance challenges must be addressed to bridge the gap between the two Romanias and converge with the high-income EU. Growth is constrained by weak commitment to policy implementation, creating a poor business environment and the misallocation of resources to politically connected firms. Equal opportunities for the poor and bottom 40 are constrained by weak local service delivery and an inability to ensure sufficient local funding because of patronage-based politics. Resilience to natural disasters and climate change is constrained by a lack of coordination between central and local authorities. As will be illustrated in the coming chapters, Romania has no choice but to address these challenges if it is to achieve sustainable and inclusive growth.

SETTING PRIORITIES FOR SUSTAINABLE AND INCLUSIVE GROWTH

A. Identification of priorities

Romania achieved an impressive reduction in poverty in the years leading up to the financial crisis, but progress has been slow since then, and a substantial welfare gap remains between the two Romanias. The past three decades in Romania have seen the consolidation of democratic institutions and an unprecedented increase in income per capita. The most dynamic firms and individuals have fully benefited from being part of the EU, with Bucharest and a handful of secondary cities becoming vibrant urban centers with growing populations and incomes. Yet vast segments of the population have been left behind and are unable to take advantage of opportunities.

Institutional challenges that are holding up structural reforms need to be addressed to unlock sustainable and inclusive growth. Weak commitment to policy implementation and influential vested interests help create an unfavorable business environment, holding back productive investment, both public and private, stunting innovation, and causing misallocation of resources. Lack of planning and poor horizontal and vertical coordination within government lead to weak local service delivery, constraining equal opportunities for the bottom 40. Finally, resilience to natural disasters and climate change, to which Romania is particularly exposed, is constrained by lack of coordination between central and local authorities.

The key lesson from this diagnostic is that, despite impressive economic growth, achieving shared prosperity and sustainable welfare improvements will remain a distant reality if Romania does not address its governance challenges. The identification of governance failures as the most binding development constraint sheds light on why economic growth continues to be volatile and non-inclusive. Concerted efforts are needed to enhance commitment to long-term policy goals, while future policies need to acknowledge and target the underlying institutional challenges. Resolving these will be a long and difficult process, but the potential rewards will be high. This would also help Romania counter the consequences of a shrinking and aging population, and allow those at the bottom to contribute more actively to economic growth—which could trigger a virtuous cycle of inclusive growth and development.

Following the diagnostic in previous chapters and extensive consultations with various stakeholders, this SCD proposes a number of development priorities for Romania that will help enhance equity and shared prosperity. The list of priorities is very long, as difficult challenges remain in many key areas. Priorities are assessed based on two criteria: (i) their potential impact on reducing poverty and boosting shared prosperity; and (ii) how critical they are to addressing the constraints that keep Romania from advancing toward its goals. The reforms that address the most binding constraints —and represent higher order priorities in terms of their relevance—are noted as being highly critical. Also, priorities receive higher ratings if they are important for the sequencing of reforms and for helping to resolve other constraints. While not a consideration for the prioritization itself, the time horizon for the impact to materialize is also indicated in the last column.

Based on these criteria, four broad areas of priorities are identified: (i) increasing the effectiveness and efficiency of the state in public service delivery; (ii) catalyzing private sector growth and competitiveness; (iii) ensuring equal opportunities for all; and (iv) building resilience for sustainable growth. These priorities will inform the World Bank Group’s engagement in Romania for the period 2019–2023.

The governance priorities are considered as prerequisites, whereas the other three areas proposed are intended to be complementary and mutually supportive. For example, promoting human capital development will not only promote inclusion, but also enhance the overall skill composition of the labor force, thus contributing positively to growth. The three priority areas are supported by a fundamental pillar on governance reforms aimed at improving commitment to policy goals, as well as policy coordination and implementation.

B. Knowledge gaps

We conclude this report with a list of key knowledge gaps that were discovered during the diagnostic. Filling these gaps would help policy makers assess the impact of policies and design more effective interventions. In what follows we include a list of topics where further research is needed to properly guide policymaking. We also indicate data gaps when relevant:

- Productivity analysis based on firm-level data. Use of panel data from a firm census or a structural business survey would allow to identify the impact of firm-level characteristics and market conditions on productivity growth. This would lead to a more nuanced understanding of the drivers of Romania’s economic growth and of its pitfalls.

- Obstacles to female labor force participation. A deeper investigation into the impact of labor market and family policies on female labor force participation would help identify the biggest obstacles and priority intervention areas and groups.

- The broader welfare impact of emigration. Available surveys do not sufficiently capture patterns of intra-EU population movements and collect limited information on income from overseas employment or remittances. More data is needed to assess the welfare consequences of high emigration on children left behind and to provide effective policy responses.

- Drivers of low geographic mobility. A systematic study is needed to explore the drivers behind the extremely low geographic mobility and how they can be addressed.

- The drivers and consequences of informality. Two household surveys are available within the last decade which allow some measurement of informal employment: the 2008 round of the European Social Survey and the 2016 round of the Life in Transition Survey. A detailed investigation of informality is difficult with these surveys, because of the limited information included and the small sample sizes. Better data would help understand the institutional factors and the drivers behind informality, from the firm and household side.

- The impact of labor market institutions on labor market outcomes. A better understanding is needed on how labor market institutions, notably minimum wage policies and employment protection legislation may impede the dynamism of the labor market and affect labor market outcomes (including the incidence of informality) of different population segments.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This report was written by a team co-led by Donato De Rosa (Lead Economist, World Bank), Yeon Soo Kim (Economist, World Bank) and Aimilios Chatzinikolaou (Senior Operations Officer, IFC), and including Catalin Pauna (Senior Economist, World Bank), Vincent de Paul Tsoungui Belinga (Economist, World Bank), Andrei Silviu Dospinescu (Consultant, World Bank), Jonathan Karver (Research Analyst, World Bank), David Bulman (Assistant Professor, Johns Hopkins University SAIS), Maja Murisic (Environmental Specialist, World Bank) and Craig Meisner (Senior Environmental Economist, World Bank). The team received guidance from Arup Banerji (Country Director, World Bank); Tatiana Proskuryakova (Country Manager, World Bank); Lalita Moorty (Practice Manager, World Bank); Luis-Felipe Lopez- Calva (Practice Manager, World Bank); Thomas Lubeck (Manager, IFC); Gjergj Konda (Principal Economist, IFC); Christian Bodewig (Program Leader, World Bank); Andrea Liverani (Program Leader, World Bank) and Rogier van den Brink (Program Leader, World Bank). The team is thankful to peer reviewers Ulrich Bartsch (Lead Economist, World Bank), Pedro Rodriguez (Program Leader, World Bank) and Carlos Rodriguez Castelan (Senior Economist, World Bank) for their comments.

Many staff contributed to this report, with inputs to specific chapters and to the preparation of a series of background notes that helped inform this diagnostic. The team would like to thank our counterparts in the Government of Romania, the private sector, academia and civil society, members of the World Bank Romania Country Team from all the World Bank Global Practices, and the IFC, who have contributed to the preparation of this report and participated in several rounds of extensive consultation events. We benefited greatly from their expertise and input in various forms. Maria-Magdalena Manea edited the report, Victor Neagu provided communications support, and Raluca Marina Banioti and Mismake D. Galatis supported the team throughout the process.

![2026 consumer trends and industry insights [Webinar]](https://doingbusiness.ro/media/covers/6979dc6c4329e_cover.jpg)